If you’re looking for a solid medieval romance where good always triumphs over evil and true love is always rewarded, then Sir Eglamour has you covered. With its dramatic battles and poignant love scenes, it is no wonder that this mid-14th century tale maintained popularity throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and even was adapted into a play (Eglamour and Degrebelle, 1444CE).

The romance follows Sir Eglamour, a “knygt of lyttyll land” (l.64) who falls in love with his lord’s daughter, Cristabelle. Despite his inferior social standing, Eglamour is the picture of knightly grace, and asks to marry the heiress. Cristabelle’s father, the antagonist of the story, agrees to the proposal with the condition that Eglamour completes a few tasks of strength and valor, primarily focusing on the slaying of several beasts. The last task is to slay a dragon in Rome, and while Eglamour is away, Cristabelle bears a son. Her evil father (who has been unsuccessfully trying to kill Eglamour with his ridiculous tests) sends her and her son, Degrebelle. The rest of the tale focuses on the reunification of Eglamour with his lover and child, and involves a magic-griffin, a ship-wreck, almost-incest, and, of course, a happily-ever-after.

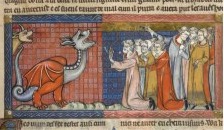

While I think it is incredibly difficult for any reader to NOT be enamored with Eglamour and his poise as a hero, I am also interested in this tale as a guidebook for mythic figures. The knight’s exploits include the slaying of a deer, a boar, a few giants, and a dragon. The dragon here (as elsewhere) serves as the epitome of the Eglamour’s tests of valor; to defeat a dragon who “walled owt of helle” (1. 723) in the heart of Christendom (read: Rome), when so many have failed before him, is the ultimate exemplification of his noble knighthood. It is fitting then, that this episode receives nearly 100 lines of consideration in the 1320 line poem. Throughout their battle, Eglamour cuts out the dragon’s tongue (though in some versions, it’s the dragon’s tale) before eventually dealing a death-blow to its rygge bon [back bone] (l. 734). While there is a lot to parse through within this dragon-battle, I am fascinated by what happens after the serpent is felled. After the dragon’s death, the whole of Rome, including the emperor, flocks to Eglamour in celebration. The city bells chime out, and the princess rushes to heal the wounded knight. And then, the crowd looks on.

They look on at the magnificent and terrifying corpse beyond them:

763 Hys sydys hard as balayne was,

Hys wynges were grene as any glas,

Hys hed as fyre was reed.

763 His sides (scales?) were as hard as whale bone,

His wings were as green as any glass,

His head was as red as fire.

They looked on as brave souls measured him:

769 They metyd hym, forty fote and mo. [They measured him, over 40 feet.]

They looked on, as men bore the body outside of Rome and buried it, gagging at the stench:

776 Mony men fell in swonyng

For stynke that from him come.

776 Many men fell, swooning

From the stench that came from him.

There’s something bizarrely clinical about this scene in the patterns of observation, of measurement, and of burial. The reader’s senses are ignited as they learn of the hard scales, the vibrant colors, the horrific stench, and perhaps an implied silence—or multiple exclamations—as the people of Rome witness this beast still and unmoving. While Harriet Hudson notes in her introduction to the poem that the dragon is the most “unnatural” of the creatures Eglamour takes on, there is something very natural about his description and about his body postmortem. There is also something natural in the way the citizens of Rome approach the corpse, as curious onlookers to a marvelous creation of something beyond themselves. By including such a scene, this text not only describes familial relations and love, but also provides a description of early understandings of the natural world.

Where to read it:

Sir Eglamour of Artois, ed. by Harriet Hudson, via TEAMS Middle English text series, University of Rochester.

or, try a short summary of the poem in Modern English via the Database of English Romance from the University of York.